Since opening its doors to a group of thirty students in 1959, Syracuse University’s Villa Rossa has been a home-away-from-home to thousands of American college and university students attending the university’s Florence program. One of the challenges each student faces upon coming to a new city is how to create a sense of place and belonging. Ultimately, each student forges a uniquely personal amalgamation of people, places, and things that gives meaning and substance to their study abroad experience. One of the places, however, that figures largely in the common experience of all students who have come through the Syracuse University Florence program is the villa itself. Day in and day out, Villa Rossa continues to serve as a unifying point of reference.

1865: The Walls Come Down

The medieval walls that had surrounded the historic center of Florence protecting it from its enemies for over 500 years, were demolished in the mid-1860s as part of Giuseppe Poggi’s reurbanization plan for the city after the 1861 Unification of Italy. There had long been a social stigma attached to the division between urban and rural life marked by those walls, and this stigma persisted in the minds of many Florentines even after they were gone. This was especially true among the nobility.

1886-1892

In 1886, Mario Gigliucci decided to design and build a permanent home for his young family of five on a small plot of land he had purchased a few years prior in Piazza Savonarola, just outside the old city walls. At that time the square was little more than a field of poppies with a statue of Fra Girolamo Savonarola in the middle. Several of Gigliucci’s aristocratic friends openly criticized the location saying it was out in the fields, too far from the city center. But Conte Gigliucci liked the idea of living neither in the city nor the country and being able to enjoy the best of both. In 1892, the Gigliucci family moved into their new home.

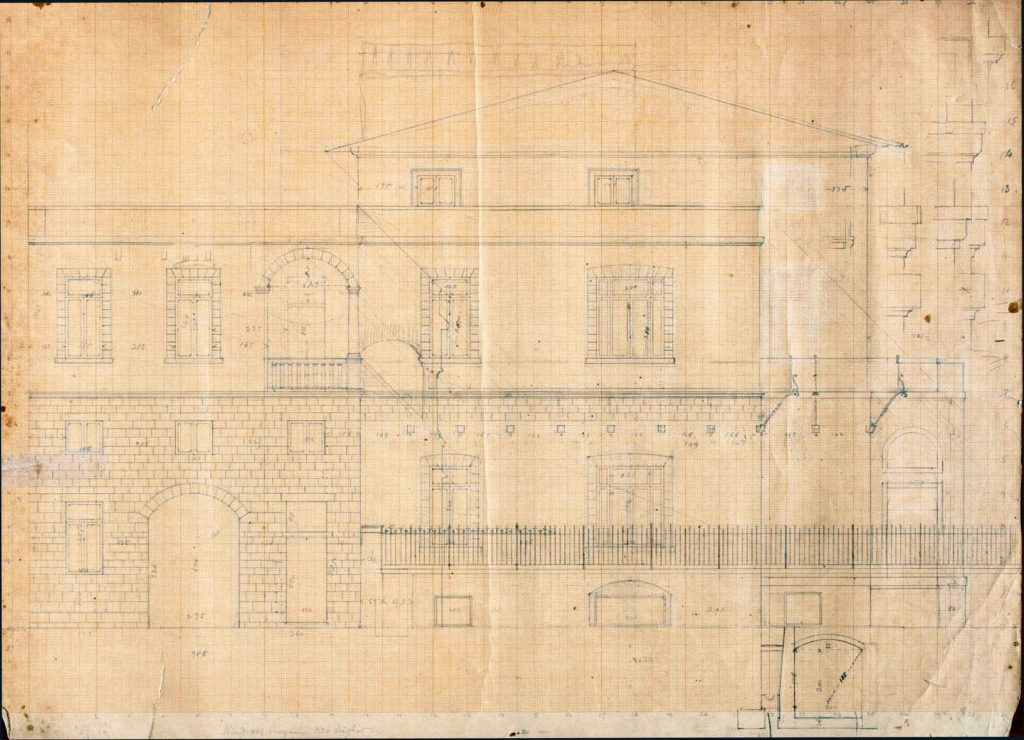

The Architecture

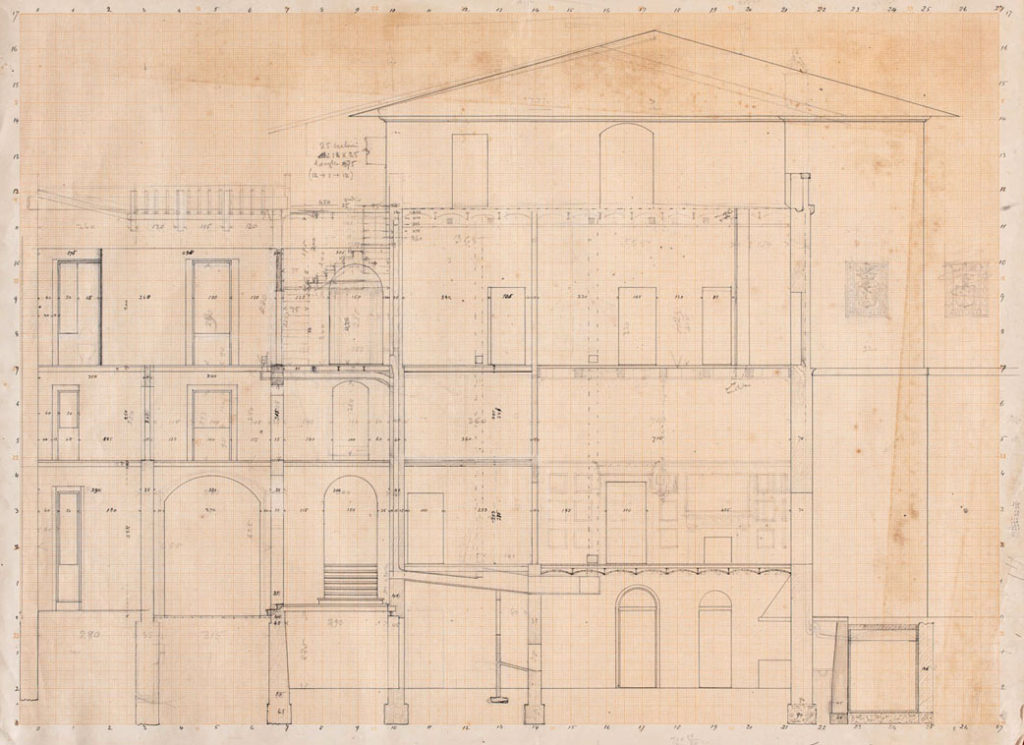

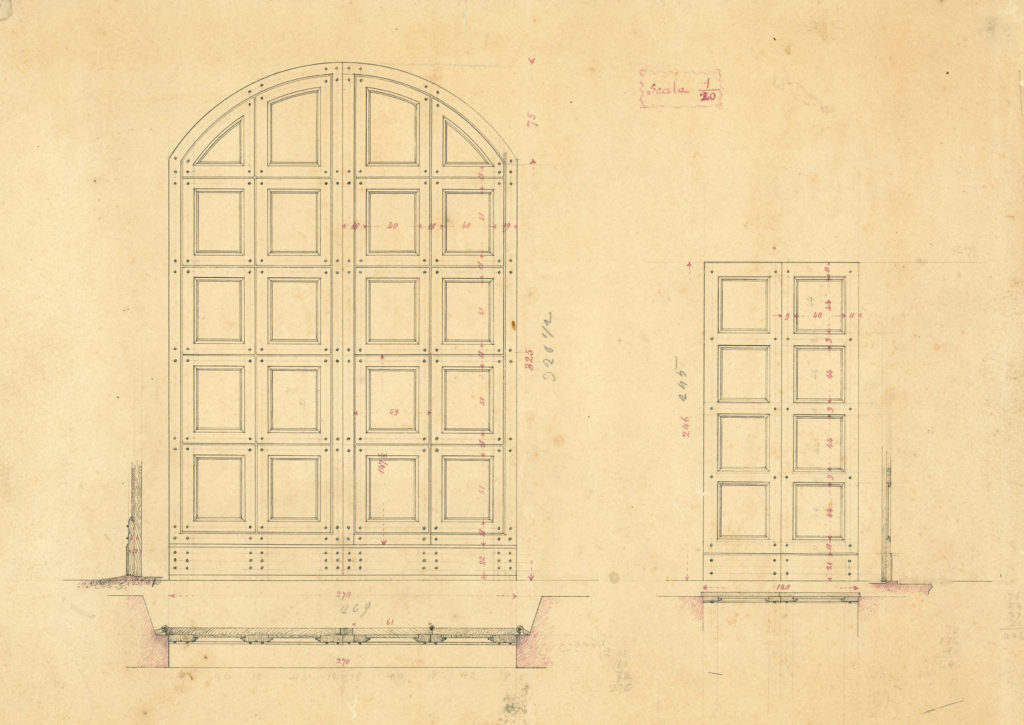

The exterior design of Gigliucci’s villa (or villino, as he referred to it) did not follow the typical scheme of either an urban palazzino or a country villa. Its asymmetrical, three-part design reveals how it differed from the unified, monolithic form of the traditional late 19th-century Florentine palazzo or villa. The exterior presents other unorthodox elements, such as the small corner loggiato over the entrance door, the walkway decorated underneath with hanging baskets that wraps around to a side terrace, and the rooftop garden that looked out over the front of the house.

Exterior: Front View

In contrast, the interior spaces follow a more traditional pattern.

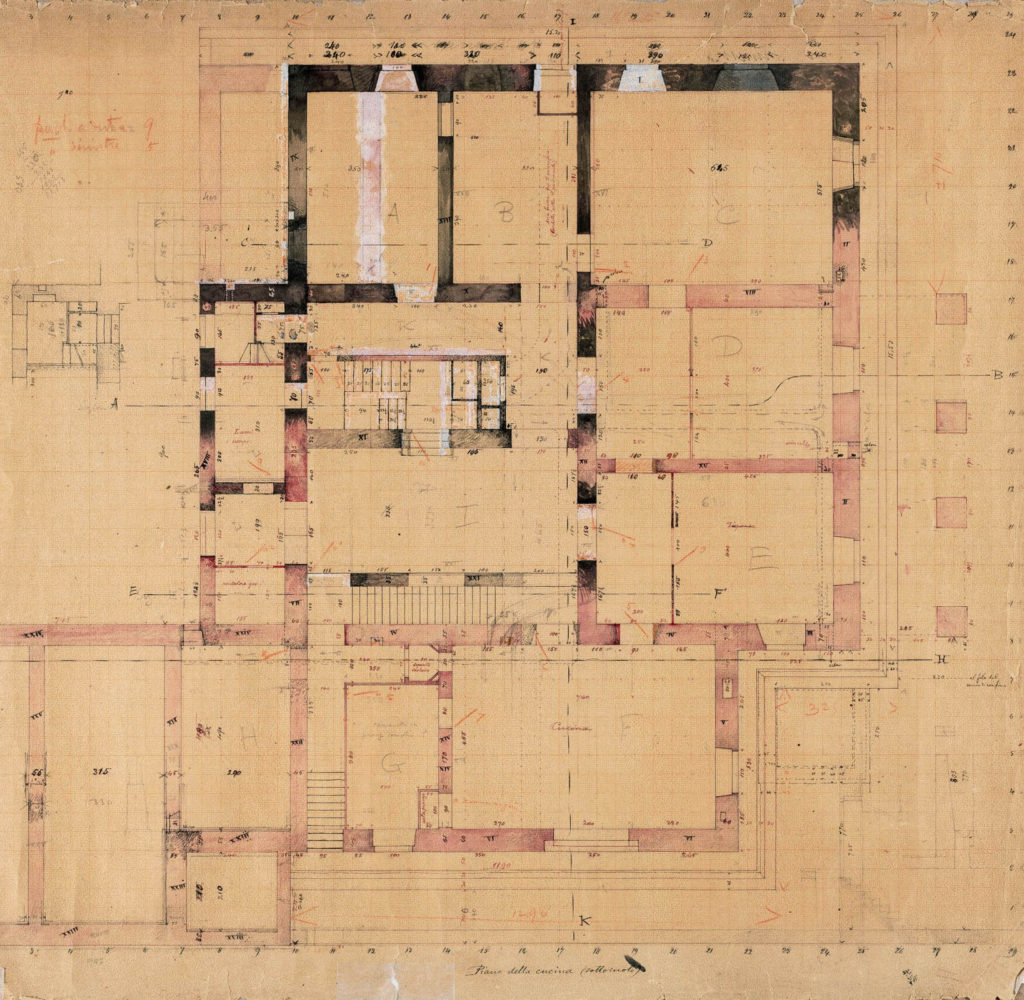

Basement Level

The basement was reserved for practical purposes such as the kitchen and storage spaces.

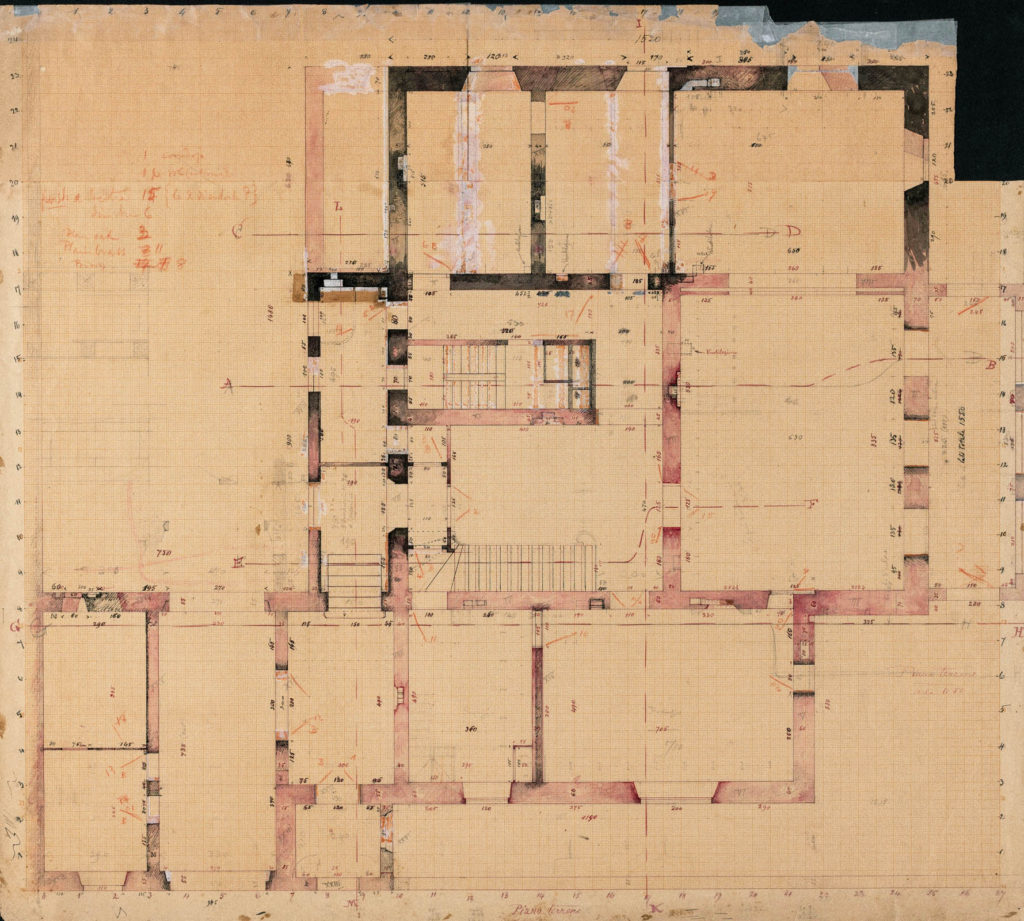

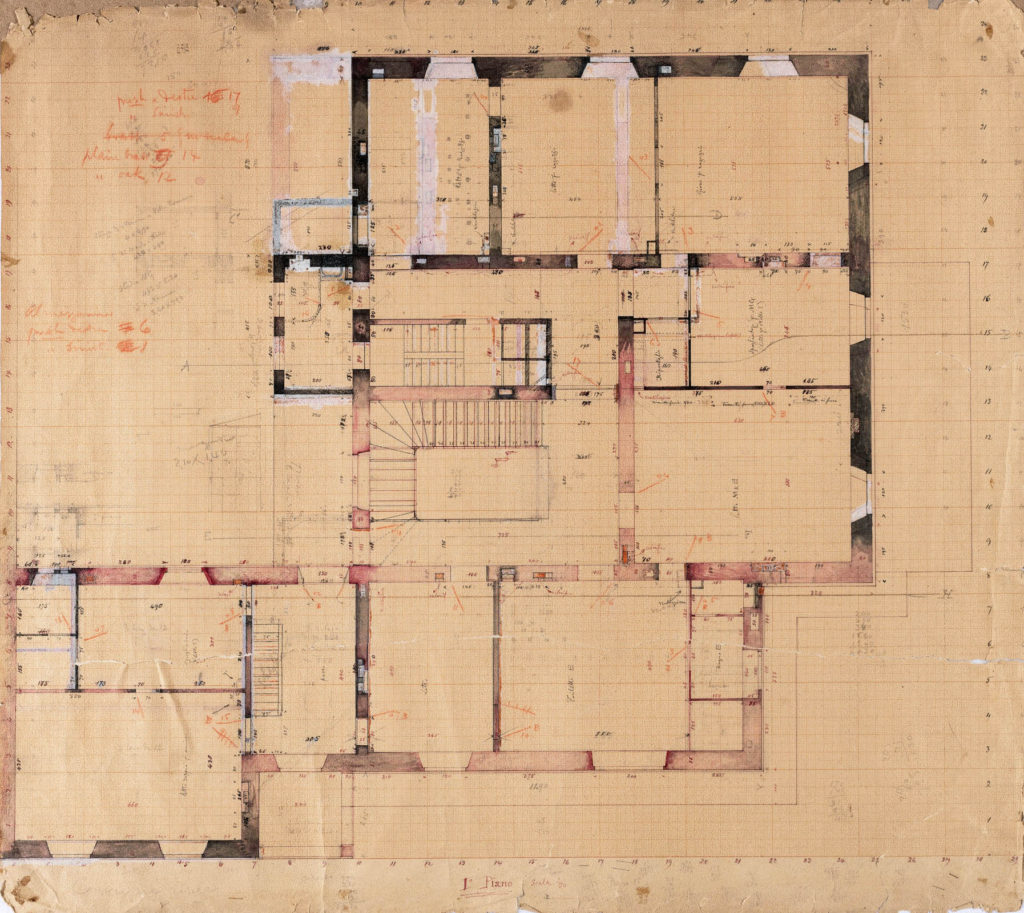

First Floor

The first (or ground) floor was dedicated largely to family life with two studies (one for Mario Gigliucci and another for his wife), a large and small sitting room, and a dining room fitted with beautifully carved wood panels.

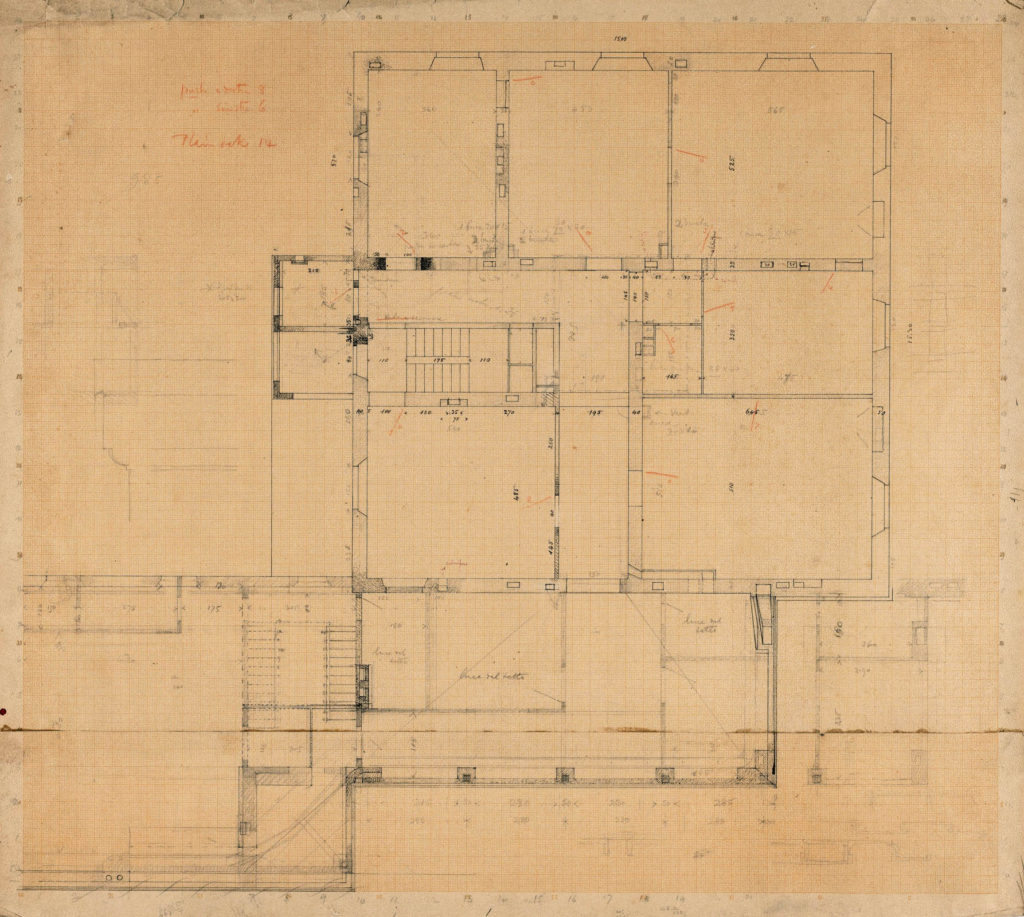

Second Floor

The second floor was reserved for bedrooms and guest rooms.

Third Floor

The top (third) floor consisted of a playroom for the children, which opened onto a rooftop terrace, and more servants’ quarters.

Staircases

From top to bottom the four levels were connected by two sets of servants’ stairs, or “secret stairs” as they were called, hidden away on either side of the building.

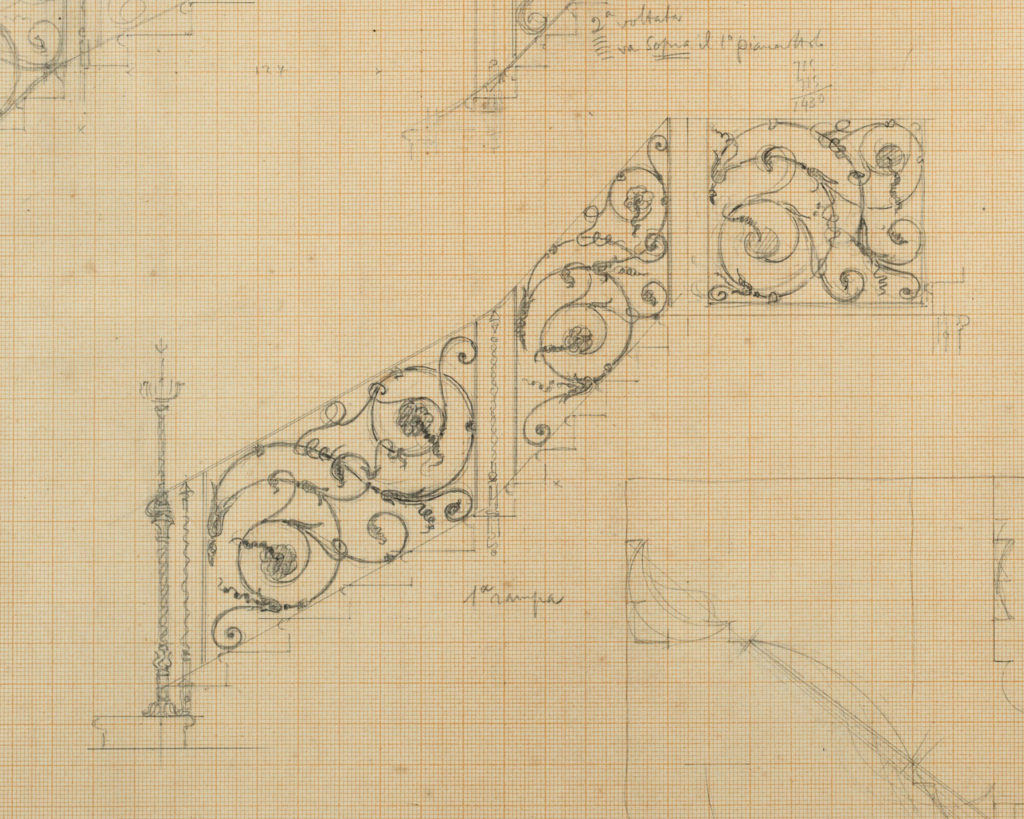

A large, elegant staircase connected the first and second floors for the family’s use.

Embellishments

Count Mario put a great deal of time and effort into designing each and every detail of the villa to create a beautifully unique environment. Though the second-story and some ground-floor rooms no longer have their original tempera paint designs, the decorations in many of the other rooms remain. In some of the former bedrooms, today used as administrative offices, one can still see the ceiling borders composed of ribbons, poppies, passion flowers, wild grapevines, and other flower motifs and fanciful patterns, reflecting the immediate rural surroundings.

The wrought iron banister of the main staircase is just one example of Gigliucci’s attention to detail.

1959 to the present

Between 1959 and now, the elegant interior and lush garden of the Gigliucci villa has provided ample space for Syracuse University to grow from the first class of 30 students to become one the largest American university programs in Italy of its kind, with ca. 650 undergraduate and graduate students per year.

Though very few of the Gigliucci family’s furnishings and effects have remained in the Villa and some changes have been made to the structure to accommodate the practical needs of the school, the spirit of the house as the Gigliucci knew it lives on. For the Gigliucci family, the Villa was the focus of everyday life and in many ways defined their ties to their adoptive city of Florence, just as it has done for Syracuse students. It is, in a sense, a place whose mission extends far beyond the boundaries of its walls as it unites the students, faculty and staff of Syracuse University in Florence with the Florentine community and the diverse foreign communities within Florence itself. Though the growth of Florence has made it more of an urban villa than one straddling city and country, the Villa Rossa continues to negotiate between two worlds, uniting generations of students and their European hosts across the Atlantic.